Potatoes are an underappreciated garden crop. People can survive on this tuber alone because it contains everything for complete nutrition. Spuds thrive in diverse soils and climates. They store well and are easy to plant and care for. Because potatoes are cheap in the grocery store, many gardeners opt not to cultivate them, but for those who choose to grow their own, deciding how to manage them can be a challenge.

Garden magazines, books, and websites are full of ideas for growing potatoes. The variety of options can be overwhelming, especially because each method has proponents who report fantastic yields and detractors with stories of failure. In order to separate the wheat from the chaff—so to speak—we carried out an experiment on the performance of five of the most popular growing methods.

Potato-Growing Methods

Potatoes are native to the Andes, where the Inca and their predecessors cultivated thousands of varieties in a complex environment: unpredictable El Niño–driven precipitation and starkly varied elevations with diverse ecosystems. Traditional cultivation involves digging trenches to create rows of soil and llama dung. Seed potatoes are buried in the dug up fill (not the trenches). A mix of potatoes are planted in the same row. This practice builds in food security: regardless of the season’s conditions, at least a few varieties will do well, even if others fail.

Western gardeners have adapted this into the trench-and-hill method. A half-foot-deep trench is dug for each row of potatoes. Compost is worked into the bottom of the trench, and seed potatoes are planted at about a one-foot interval; I use the traditional spacing method of walking heel to toe in the trench and dropping a seed potato in front of each toe. The potatoes are covered over with mulch and soil. As they grow, the soil between the rows is mounded up around the emerging plant, creating hills to help support the stalks and cover the tubers to prevent greening. Harvest is hard work using a spading fork and redigging the trenches to turn up the new potatoes.

A more recent method involves planting the seed potatoes right on a surface of prepared soil, to be covered by compost and mulch. Some add a layer of newspaper or cardboard as a sheet mulch below the straw or woodchip mulch. As the plant grows, more mulch is added around the stems in the same way as the trench-and-hill method. The stark difference comes at harvest time: the mulch is pulled back and the tubers are plucked off the ground with no digging required.

Other methods create a container for the plant. Bags, plastic buckets and totes, barrels, wooden boxes (called“towers”), and even stacked car tires have been used to grow potatoes on the ground, patios, and balconies (tires should be avoided, however, because they leach chemicals). The idea is that if it is good to hill up around the plants, growers can bury plant over and overusing containers with high sides, creating a deeper root structure and greater yield. This method is more flexible and easily used by those without access to soil they can trench. To harvest, the containers are tipped over and the spuds are collected. Some towers are designed to be harvested without killing the plant: sides are made up of horizontal boards, allowing the roots to be accessed without upsetting the plant by removing lower boards.

The Experiment

We tested five methods to determine which is the most productive and least labor intensive for the small-scale grower. The first method was trench and hill, which we considered our “control”group. Then we tested two surface-planting methods: straw mulch and straw mulch over newspaper. We also tried two containers: bags and wooden towers. We had about a century of potato-growing knowledge taking part in the study: our test group consisted of ten growers, ranging from farmers’ market growers to homesteaders and backyard gardeners across southern Wisconsin.

We kept other variables consistent except for the growing method: Each grower set aside five small beds (8 × 8 ft each) in full sun. We planted 3 lb of seed potatoes (eighteen plants) in each plot. Each plant got three quarts of organic compost (Purple Cow Activated Compost, 0.7–0.3–0.3)at planting and another quart while growing. The plots in each location were mulched with two rectangular straw bales and got the same sun, rain, and attention.

Throughout the growing season, growers noted down the time worked on each method and if they weeded, watered, hilled up mulch, or picked Colorado potato beetles. At the end of the season, we harvested the plots, weighed and counted the yield, and totaled up the time it took us for each.

The Results

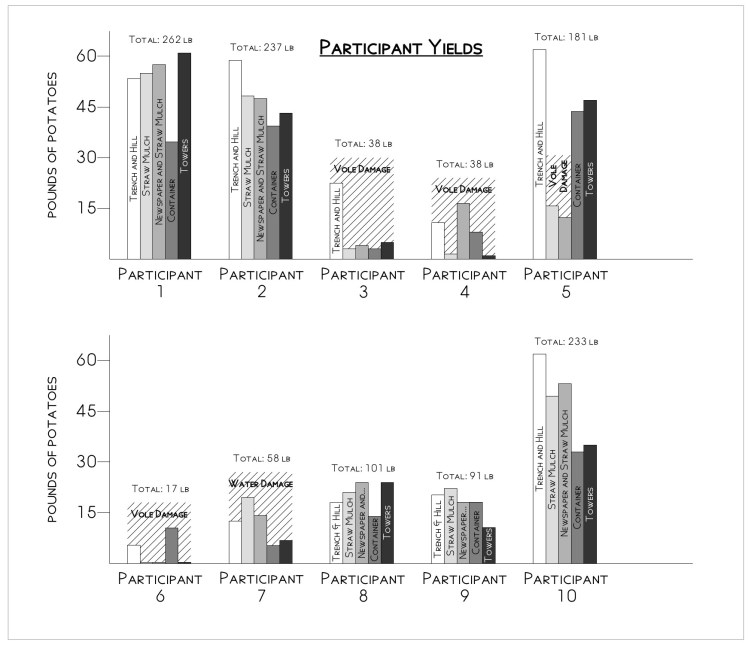

In a word, our results were mixed. We looked not only at yield but labor and what type of labor as well as cost. The results can be divided into two groups: all data and uncompromised data. Four participants had voles and/or standing water damage some of their crops, which make their results difficult to interpret, but when taken together, the “all data” statistics may be more indicative of real-world results. On the other hand, if voles and low-lying areas can be avoided, the “uncompromised data” may be what a gardener can expect.

The most productive method was trench and hill. We got an average of 1.81 lb of potatoes from each trench-and-hill plant (minimum 0.31, maximum3.44 lb) across all participants, but an average of 2.54 lb from those plots not devoured by voles. The straw mulch, straw mulch over newspaper, and potato towers returned about a half a pound less per plant on average whether from all participants (1.31, 1.38, and 1.30 lb respectively) or uncompromised ones (1.96, 1.98, and 2.05 lb). The bag containers were easily the lowest yielding at just over a pound (1.17 lb) for all participants and a bit more (1.70 lb) for those who were vole free. All plants started with a seed potato weighing 2.7 oz on average, meaning even the lowest average yielding method returned a seven-fold increase while the best plots returned over twenty times the seed weight in edible taters.

Yield isn’t the whole story, though, as labor is as much of a gardener’s investment as the cost of seeds and materials. On a per-plant basis, all gardeners averaged the least time on the straw and straw-over-newspaper methods (8:39 and 7:42 min, respectively), a few more minutes on bags (10:30 min)and trench and hill (11:21 min), but twice as much time on the towers (16:59 min) because of the construction of these containers.This means that even though the trench-and-hill plots produced about 139% more than the two surface-planted methods, they took 140% more time, washing out any advantage. If we look at the uncompromised yields, the gap widens, and gardeners were spending almost 178% more time to grow only 130% more pounds of potatoes per plant in the trench and hill plots.

We can also report on the types and average amount of work for each method. We had plenty of rain in 2018, and most participants watered once (0.63 times over the season season, on average). Bags and towers required the least weeding (averaging 1.75 and 2.00 times, respectively). The straw-mulched plots required a little more weeding than the newspaper-and-straw plots (2.25 vs. 2.13 times per season). The trench-and-hill plots required the most weeding, but not by much (at 2.88 times per season). On average, all plots were hilled up between 2.50 and 2.88 times and cleared of pests (potato beetles or voles) between 1.50 and 1.75 times, which amounts to no real difference among the methods.

Finally, the methods varied in cost of materials. The trench-and-hill, straw, and straw-and-newspaper methods all cost $2.18 per plant. This includes a 2.7-oz seed potato, 4.0 lb of compost, and 11% of a straw bale for mulch. The bag container would have cost $3.18—the additional dollar for the 50-lb grain bag—if we were not able to get the bags donated from the Wisconsin Brewing Company. The potato towers, though, cost $11.61 per plant; each tower held up to four plants. Although they received the same amount of seed potato, compost, and mulch, they also had frames built of lumber and screwed together, adding $9.21 to the baseline cost. And while one participant had strong yields from their tower (3.38 lb per plant), most towers produced an average amount of potatoes when not inhabited by voles—one tower even had a vole nest with squeaking babies when we harvested the tower. Unlike the other methods,however, the towers can be used for a few years, so this cost could be divided by two or three to amortize the lifetime cost.

We measured other variables that did not seem to affect yield or labor. Our soils ranged from loam to clay, but counterintuitively, soil morphology had little effect on the yield or size of potatoes. When dividing the total yield by number of potatoes for each plot, we found the average tuber size was also not greatly affected by method of planting: trench and hill potatoes averaged 7 oz each while the surface plantings, bags, and towers hit 6 oz. Other variables that played no discernible role included previous weed pressure, whether or not a bed was virgin soil or established, or what the previous crop was.

The Take Away: Context is Everything

We did not find that one method was the clear overall winner and how you choose to grow potatoes comes down to your situation. Access to land, presence of pests, total yield required, cost, and labor considerations might point one grower to use bags, another to use surface planting, and another to trench and hill. Our results fall into two categories: data-derived recommendations and anecdotal observations.

Our study results suggest three different potato methods depending on a grower’s resources and goals. If a grower doesn’t have access to land but wants to grow potatoes on a patio or other outdoor surface, bags with compost and mulch are the clear winners over potato towers. First, one can grow sixteen potato plants in bags for the cost of every tower, which holds four potato plants. Although bags had the lowest yield, they also took less time to plant and tend than towers. We did not test other containers and perhaps barrels, large planters, or other containers would be more long-lasting than bags. We used recycled grain bags, which disintegrated in full sun and should be avoided to keep plastic shreds out of the environment.

If a grower has space to plant potatoes in the ground, the choice between using trench and hill or surface planting hinges on space, reliability, but most of all, presence of voles. If space is at a premium, reliability is vital, and/or voles are present, the trench-and-hill method would be best. It had the highest yield per plant and most resistance to voles; only three of ten participants had voles in the trench-and-hill plots, while only five of the ten surface methods stayed vole free. On the other hand, the trench-and-hill method required more work for each plant than planting on the surface with newspaper and straw, and if voles and space are not an issue, this surface-planting method is the clear winner. Although it yielded less per plant than trench and hill, it was much less work and therefore more efficient when comparing time to grow each pound (4:15 vs. 2:37 min per pound, respectively).

Trials often find results that were not in the original research design, and this experiment is no exception. Since we did not set out to test these observations, they are offered as anecdotal suggestions and could be validated in a controlled study. One participant had a wetter location than the others and in that case, the trench-and-hill plot suffered rot and severe loss, while the surface plantings had seemingly unaffected yields, likely because they were above the waterlogged surface. This result may hold for containers, but this participant also had vole issues that targeted the bags and towers,thus obscuring the result. Voles were the worst pest in our trial, although a few participants did have to hand-pick Colorado potato beetles off of each of the plots. After harvesting plots in ten locations, a pattern of vole damage did appear: potato plots on the edge of gardens (adjacent to lawns, forests, or bushes) had most of the vole damage, while potato plots in the middle of gardens, with a “moat” of bare earth, seemed to fare better.

Our participants suggested a few ways to optimize the methods we used that are worth mentioning. One market grower plans to cultivate their potato bed, set seed potatoes on the surface, cover with compost, and then unroll a large, round straw bale over the plot, burying everything in 8 in of straw. This may be an even more efficient way for large-scale planting of the surface method. Another grower, who puts up hundreds of pounds of potatoes each year for his family, uses cardboard and woodchips instead of newspaper and straw to cover his potatoes. Although the voles attacked the trial potatoes, his own adjacent crops with the cardboard and woodchips were vole free. Another grower also used cardboard and woodchips between the rows and straw over the potatoes with similar results. In both cases, these plots were virtually weed free.

Potatoes are a worthwhile addition to most gardens and a must for those interested in self-provisioning, as these tubers pack one of the best returns on investment in terms of space and labor. Additionally, potatoes store well with no additional canning or preparation required. As a staple, taters can bulk up a dish flavored by your other garden products. Our hope in this study was to point gardeners to a method of growing that fits their needs and conditions without having to try out different schemes year after year.

We welcome the input of other citizen scientists who want to trial new potato-growing methods against controls. For those that want to add to our body of data, we encourage you to read our more technical summary (coming soon), view the complete data, and watch the video available at https://lowtechinstitute.org under the “research”tab, as this article provides a only brief overview of the methods and results.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyOr join our community and support us on Patreon.

This research was carried out thanks to a grant from the United States Department of Agriculture’s Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education program (project number FNC18-1128).

6 thoughts on “Potatoes Five Ways: A Trial Looking at Different Potato-Growing Methods”